We’re all a bit too familiar with membership cards of supermarket chains, like Walmart or Albert Heijn, the largest supermarket chain in the Netherlands. Besides the advantages these cards have for the consumer, they have a lot more advantages for the supermarket chains. They apply advanced data science techniques to the data gathered with these cards to figure out where to put products in the store, what products to put next to each other and what products to put on sale together.

For 6 months I interned at TAPP, a company that tries to bring the same insights to the hospitality industry. Because there are no membership cards for bars (in most cases), we do this by analyzing the products on receipts. Because of the inconsistent offerings at venues, TAPP focuses almost exclusively on drinks, due to the clearly branded single units used. Doing this gives us a very detailed view of the market for drinks, allowing us to see, for example, market shares and revenues for specific sodas, liquors and beers.

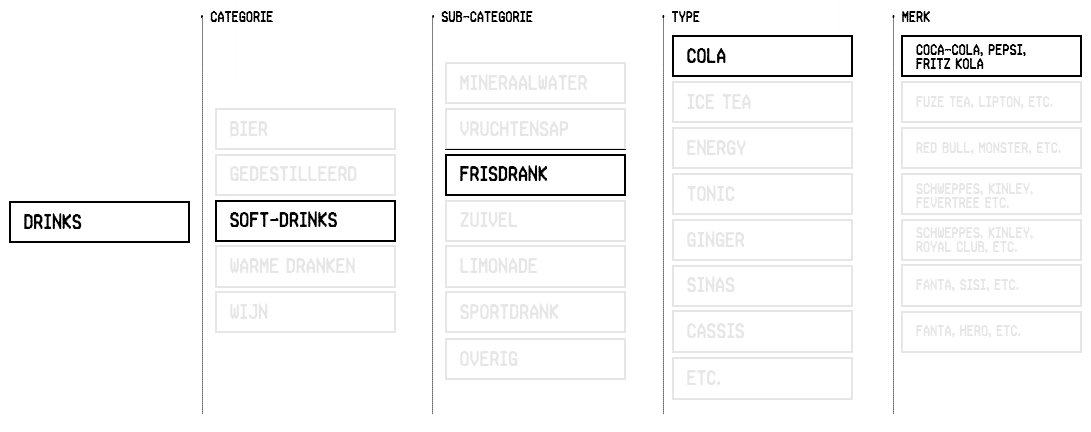

Every consumption we receive is connected to a product. Before we can use products in our analysis, a product needs to be ‘tagged’. This tagging means we need to specify what a product is, because the description on a receipt is not enough for insights. A description might be ‘Hot choco’, and to use this for our analysis we need to specialize our five tag levels, which are group, category, subcategory, type and brand. This is also the hierarchical order, so a category has zero or more subcategories which has in turn zero or more types. I purposely omit group because the group tag consists of the values ‘Drinks’, ‘Food’ and ‘Other’, and we only have categories for ‘Drinks’, because of our focus. The hierarchy is visualized in the image below.

Sounds great, so whats the problem?

Well, a product is identified by the unique combination of the venue, the description and the price. This means a coke in small, medium and large are three different products at a single venue. And this goes for every venue. This means that when connecting with a new venue, we get somewhere between 300 and 2000 new products. These all need to be tagged, which was up until now all done manually. You can image this is a very slow, error-prone process.

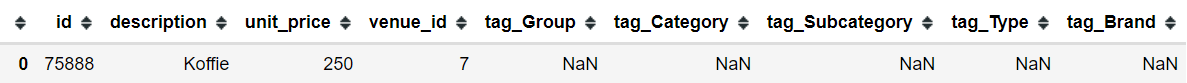

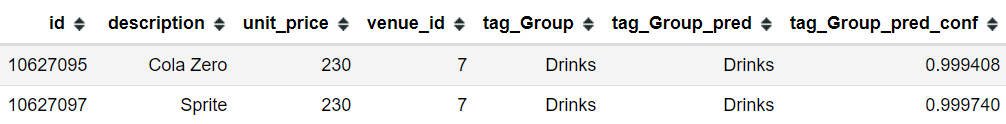

And this is where the fun begins. Because this is a very well suited case for some good ol’ machine learning. The goal is to substitute the human labour in the tagging process by a machine learning model. In the image below you can see the data we are working with. Variables that are useful for classification are the description and the unit price. We start of without any of the tags and want to end with them filled in. Because sometimes we just don’t have enough information for some tag, the model also has to be able to predict empty values. This is also visible in the images below, where the brand is left empty because the description ‘koffie’ (coffee) does not give us enough information to fill this.

Because the hierarchical structure of our tags holds a lot information, the best approach seemed to classify each tag separately, starting at the top with group and working our way down to brand. This way, lower level tags can use the higher level tag information for their predictions.

There is now way around getting a bit technical, so if that is not your thing you can skip to the results.

Approach

There are two parts to solve this problem. First, we need a model that is capable of reliably predicting these tags. Second, we need to implement this model in our current AWS based infrastructure.

General

Due to our data diversity, this is quite a complex problem. There is natural language processing (NLP) involved in handling the descriptions, as well as our tags. The tags can be regarded as either text or categorical variables (but we’ll see soon this doesn’t matter). The price is fairly simple, and we’ll just take the normalized price as input. Because we have different types of input, I opted to use a model with multiple inputs. I was most comfortable with Keras, and their functional API supports multiple inputs, so I chose this for implementation. Also, because we are tagging each layer separately, there will be a ‘different’ model for each layers. I’m putting different in quotation marks because the model architecture will be the same, but the weights will be different.

When there is NLP involved, two things are generally going to happen.

Tokenize the words (‘Cola’ -> [23])

Use word embeddings ([23] -> [0.3, -0.8, 0.7, 0.4, 0.1])

The tokenization required some creativity, because the descriptions need to be split on a space, whereas the tags should not (e.g. ‘Mineral Water’ is one tag). So two tokenizers are used. The problem is that both tokenizers use (partially) the same range of number, meaning that ‘drinks’ and ‘Choco’ can have the same token (unique number). This will be talked about more below.

Word embeddings

There are many different approaches to the word embeddings. There are very recent and advanced representations like BERT and ELMo and a little bit older representations like GloVe and Word2Vec. We can use these pretrained weights, but because our vocabulary has a very slim overlap with normal English, this probably does not improve our result much if any. So I decided to train the embedding layer myself, and with almost 150k descriptions, we can get pretty good representations. In Keras, word embeddings are implemented by creating a fixed size random vector, which is then optimized by training. This vector captures no information about context or position, meaning a lot of information is lost. But because we are doing classification, which doesn’t require these things, this is not a big problem.

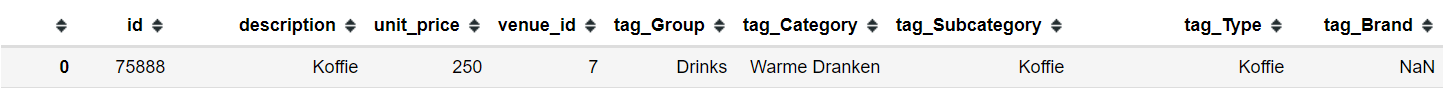

One thing to consider about these vectors is that some recent implementations of categorical variables are doing the exact same thing, most notably the authors of Fast.ai. A value is converted to a fixed size vector, to give the value a richer representation, which is then optimized by training. Now, Keras doesn’t have this categorical variable specific approach, but we can just use the same embeddings al the sentences. Because in this case, the representations are the same. To visualize the difference, look at the image below. Here, you can clearly see that the word2vec embeddings capture semantic similarities between sentence b and c, whereas the embeddings trained from scratch to not.

RNN or CNN?

I opted to try two approaches. Because there is NLP involved, using a recurrent neural network (RNN) with LSTM layers seems like a good idea. All the current state of the art language processing is done using recurrent network with LSTM layers. LSTM layers have, simply said, a memory which they can use to remember was words it has seen previously. This gives them the capacity to find word relations that are close together but also further away and makes them very powerful for language processing.

The duplicate token problem I raised earlier really hurts the LSTM performance, because it is very confusing. I solved this by creating a separate input for the tags. So the double tokens still exist, but they are never seen together. I also created a separate input for the price, where no embedding was needed. The result is a network with three inputs, one for the description, one for the parent tags and one for the price. The description and tags both go into a embedding layer and an LSTM layer. The result is the following network.

Because our texts are very short, I also wanted to try a convolutional neural network (CNN). Whereas LSTMs are very good for finding relations between words further apart, convolutional layers are very good at finding word structures closer together. Combined with pooling layers we can even detect certain structures in sentences. The same goes for the ‘categorical’ values of the tags. CNNs are already very well known from computer vision, where they have been the state-of-the-art for multiple years.

The duplicate token problem is much less of a problem with the convolutional approach, because the context of a word matters more than the word itself. The odds of finding the same structures with the same tokens in both the tags and the descriptions is marginal with a vocabulary of 16000 words for the descriptions and the 1300 tag combinations. So, if this is not a problem, the tags and descriptions can just be concatenated when doing convolutions. This approach also has the capacity to see certain relations between tags and description. The result is a model with only two inputs.

Implementation

At TAPP we use two services primarily for our data pipeline: AWS and Airflow. Airflow is a great, open source and free tool to manage data pipelines and the ETL process. If you want to know more about Airflow, I recommend this article.

Every part of our infrastructure lives inside a docker container. Using ECS, we can easily manage our services and it allows us to quickly scale up and down, depending on our needs. Additionally, moving our infrastructure to different environments is relatively easy, for example a local development environment.

Predicting or training this model are in our system batch operations, which need a lot of compute power for a short time. For this reason, I opted to implement them using AWS Batch. AWS Batch only supports jobs as docker containers, which is nice because we are already working with those. These jobs are ran by an Airflow DAG which schedules the job using the BatchOperator. This model was the first neural network that was implemented which had one big problem: there was no existing infrastructure for using GPUs. Using a GPU on AWS batch requires a couple of things.

An EC2 instance with a GPU. I opted to use a p2.xlarge instance, which is on of the cheapest GPU instances and features an Nvidia Telsa K80.

This process requires a GPU enabled Amazon Machine Image (AMI), which are the virtual machines Amazon uses for their instances. Now, there are a couple of GPU enabled AMIs around, most notably the Deep Learning AMIs of Amazon itself, which feature a whole range of preinstalled deep learning libraries. Because we are using docker to run our batches, we do not care about the preinstalled deep learning libraries, but rather much more about the installed CUDA and Nvidia Drivers, that allow us to do GPU operations.

To run GPU operations in docker, one needs to set the docker runtime to ‘nvidia’. To do this by default, we need to edit the AMI and save it as a custom AMI. We can then use this custom AMI for our AWS compute environment.

Create an AWS Job Queue.

Create an AWS Compute Environment with the custom AMI, which handles jobs from the job queue.

After this is all done, we find ourselves a nice docker image which has the required CUDA libraries and Nvidia drivers installed, along with our desired python version (3.6.x). This actually took some time, because the official TensorFlow images are all python 3.5 (or 2.7, but our codebase is in python 3). The images I settled on was Deepo, by the user Ufoym. Using this in its python 3.6 variant with GPU support worked wonderfully, and required a us to only set environment variables and install some additional python packages during building. Requiring little additional software kept the build time and CI/CD pipeline speed to a reasonable level as well.

In this scenario, training the network really needed a GPU. However, the predictions can be done on just a CPU. This is great, because for that we don’t need the custom AMI and separate EC2 instance. We still do the predictions using Batch, but run them on the same machines we already had available.

Model persistence between training and predictions is done using S3. After training, the weights and tokenizers are uploaded to S3, which are then downloaded before doing predictions.

Results

Both approaches to the problem worked fairly well, but it turned out the convolutional approach outperformed the recurrent approach by multiple percents in some tasks. In the table below the results are compared and it is clear that the convolutional approach outperforms the recurrent approach by significant margins in the group, type and brand tasks. The increase in brand recognition is especially impressive, with over 4% higher accuracy and an error reduction of 48.5%. With higher accuracy in every task and lower convergence time, the convolutional approach is clearly the stronger candidate for this task. Due to the short descriptions and semantically categorical values of the tags, the natural language capacities of the LSTM cannot flourish.

Results of both approaches next to each other. The columns indicate the accuracy for that specific task. It’s clear the convolutional approach has higher accuracy with lower convergence time.

Results of both approaches next to each other. The columns indicate the accuracy for that specific task. It’s clear the convolutional approach has higher accuracy with lower convergence time.

Lastly, the data had big effects on the results. During my time at TAPP, the manual tagging continued, some labels were added, some removed, some relationships were changed. Combined with the human error that was present in the manually tagged products, this has a significant effect on the results. The categorization is still not completely finalized around aggregate products with descriptions like ‘open bar’ and combined products, like cocktails or mixers like Jack and Coke. These products are tagged as two separate products, where one has the other as a parent product. Whether the child product’s group is tagged as drinks or others is still a point of discussion. The same goes for product notes, like extra sauce on fries which are also tagged as a separate product, and where the same discussion is present but for whether it should be food or other. The (partial) automation of this tagging, paired with removed errors from the dataset should increase the model performance even more, and I think it is very feasible to get to 99% accuracy in some tasks, but the humans need to figure out how to perform this task before the machines can learn from it.

Because these results are not good enough to replace humans, I implemented a way to interact with the model using the old tagging process. Previously, a table extract is made, sent to the taggers, tagged, sent back and then re-uploaded to our data warehouse. The best way to implement the model is between the extraction and sending to the taggers. In the extracted file, there are columns added for each tag with the model’s prediction and its confidence. If the model is very sure (above 0.99 confidence) the prediction is already filled into the column the human taggers are going to fill. If the confidence is lower, the prediction can be regarded as a recommendation for the taggers. The result of this is as follows, where I removed the other tags for simplicity. Because the confidence is higher than 0.99, the prediction is already filled into the tag. Otherwise, tag_Group would be empty

Future Work

Sadly, I was not able to do everything I wanted. Among these are ideas that only recently occurred to me, when it was too late to do in-depth experiments. Even though I said earlier using pretrained weights would likely not yield much improvements, it should be checked out to confirm my hypotheses.

Additionally, in my convolutional approach I used only one convolution layer. To bridge some of the distance gap that is present using convolutional layers it might be very fruitful to add more convolutional layers with pooling in between. This way, higher order sentence structures or relations between tags and words can become apparent that are currently lost.

Curious?

If you would like to know more about this project, please comment or send me a message on LinkedIn or hit me up on twitter.